Between Pragmatism, Tolerance, and Critical Scholarship

Louis Menand published The Metaphysical Club in 2001, right before the 9/11 terror attacks altered the course of the 21st century. In his conclusion, Menand attempted to explain why the ideas of John Dewey, and the 19th century pragmatists who influenced him, William James, Charles Pierce, and Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., were having a resurgence at the end of the 20th century, shortly after the end of the Cold War. Menand claims that this pragmatism and overarching philosophy of tolerance, which came out of these original philosophers' terrible experiences with the Civil War, were essential for a functioning democracy. Democracy was having a moment in the late 20th century, as former Soviet republics attempted to find their way on their own, and decolonized African nations claimed the right to chart their own destinies.

Tolerance is not an easy path to chart, and it is not entirely clear whether its compromises require a compromise with injustice as well. Still, as Menand noted in his study of the 19th century pragmatists, it seems to be the only philosophy that avoids large scale bloodshed.

Reflecting in the American Leader back in 2023, I noted that the role of historical education in a democracy ought to be to help people govern themselves better -- to help them make decisions that will lead to more fair and just outcomes within their society. Clearly, my orientation toward public history comes from my own subjectivity and the fact that I grew up in the 1990s, that period after the end of the Cold War during which "Culture War" politics led public historians to seek compromise and validation from the public. Those same public historians had come of age during the 1960s and 1970s, a period in which the critical scholarship of the New Social History reflected the ethos of a period less tolerant of injustice and more committed to advocacy.

When the New Social History met the resurgent pragmatism of the 1980s and 1990s, anthropologists studying the work of public historians at Colonial Williamsburg, Lowell National Historic Park, and Baltimore Voices, observed how the institutions and economic systems in which these historians worked seemed to dilute the potency of their social criticism. Despite their sympathy for the intentions of these historical workers, Richard Handler, Cathy Stanton, and later, Mary Rizzo, all observed that critical scholarship seemed to melt away when faced with social and economic pressure to create, as Handler put it, "mimetic realism" and "good vibes hospitality."

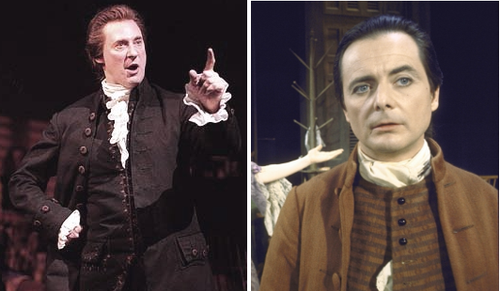

Where does this leave public historians 20 years later? Having just spent the past two months intensively studying for comps (with another month to go!) I'm steeped in critical scholarship right now. And yet, I still have my lived experience of working in museums, dealing with the realities of balancing audience expectations and funder preferences with new scholarship and critical perspectives. I'm more convinced than ever that a functioning public sphere (that mythical fourth estate of independent journalism, dynamic scholarship, and disinterested debate) is more important than ever if we want to be good ancestors and keep governing ourselves. Publics, and all of Nancy Fraser's "subaltern counterpublics" need places to deliberate and advocate. We neither want to come to blows nor do we want to settle for a status quo that un-solves our problems and hoards resources while people "reek of discontentment" to quote my favorite fictional version of John Adams. Critical scholarship should be there to help people see the problems that need solving and reckon with the legacies of the past.

|

| William Daniels and Brent Spiner both played John Adams in versions of the Broadway Musical 1776 |

I don't know how to tackle this paradox. Critical scholarship is easier to produce than ever and harder to implement. All I can do, I guess, is keep learning, and writing, and living in this moment as best I can.

Comments